The Whitman Institute advanced social, political, and economic equity by funding dialogue, relationship building, and inclusive leadership. Our focus and approach evolved from our founding in 1985 to our closing in 2022, so we thought it important to provide some of the context for our journey.

A Reflection from Co-Executive Director John Esterle

Over the years, when I talked about The Whitman Institute’s origins and history; my relationship with its founder, Fred Whitman; our trajectory after he passed away – people often said “you should tell that story.”

As TWI draws to an end, we don’t see the need to compile a detailed history of the foundation, but we did want to paint a general picture of our time on the stage so to speak. Because I was so intimately involved in TWI’s evolution, we decided I should write in my own voice.

In doing so, I’ve tried to be tactful and respectful in drawing back the curtain on some personal details regarding our early years; details that I think provide needed context for TWI’s founding and development. In a field where both funders and nonprofits are incentivized to always “look good” we think it’s important to be somewhat transparent about just how messy and complex an organization’s story can be.

I begin with the genesis of my own professional interests.

Starting with an Episcopal youth group in high school where we regularly shared and explored our thoughts and feelings, I was drawn to the power of group process. Undergrad and graduate degree programs, followed by my work with a pilot nonprofit project, fueled my interests in small seminars, interdisciplinary thinking, and the role the media plays in shaping perceptions and viewpoints.

Consequently, when I came to The Whitman Institute in 1988, I knew I had found an institutional home, albeit one with self-described “morale problems.”

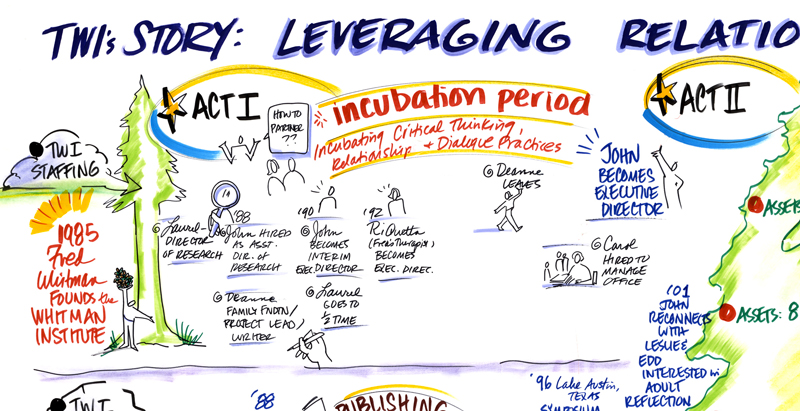

TWI's Story: Leveraging Relationships, Dialogue and Equity for Social Good

Act I

In 1985, at the age of 71, Mr. Whitman founded TWI as a small, operating foundation to explore how to help people improve their everyday problem solving and decision-making. His core question was how the interplay of thinking and feeling affects our choices, actions, and relationships. What underpinned this question was a search for answers to come to terms with his own painful past; a past that included mental illness and suicides in his immediate family, as well as a lifetime of instances where he felt irrationality and closed-mindedness ruled the day (as is not uncommon, he was better at seeing those traits in others than in himself).

He recognized that his most personal questions were also enduring philosophical and psychological ones. He hoped that TWI could offer practical information and tools to the public while adding its voice to those who advocate for the importance of teaching people how to think as opposed to what to think.

Fred had a sharp, roving mind and a knack for asking good questions. He was passionate about TWI and wanted it to be both serious and playful in carrying out its mission. How to find the right words to capture that paradox was something that proved elusive for him.

I always liked Fred’s framework for TWI to “specialize in being generalists.” That sentiment guided our initial work in producing literature reviews and program profiles on a range of topics. Fred’s resistance to focusing on any one area, however, plus the lack of any real plan to broadly disseminate TWI’s work, soon led staff and consultants to get discouraged about whether their work really mattered.

And that’s the point where I entered the story, three years after TWI’s founding.

ThinkAhead was the first project I took the lead on. It featured forums with a broad range of academics, business leaders, teachers, and writers who explored how to develop the kinds of thinkers needed to navigate a world of increasing complexity and rapid change. For a variety of reasons, the word “focus” was foreign to Fred’s vocabulary, however, and once the project gained some momentum, he decreed we needed to go in a new direction. This became a familiar pattern with whatever we were working on.

Understandably, tension surrounded such shifts in direction. The dance between a founder who needed a lot of personal attention and made program decisions on a whim—and staff members who wanted autonomy to act in the world in a more sustained way—became a complicated, and ongoing one. Over time, I learned how to practice those steps skillfully, and in 1999, became TWI’s executive director.

TWI’s most successful projects were Family Foundations at Work, which looked at how family dynamics affect the decision-making and management of family foundations, and Conversations with Critical Thinkers, which invited leaders in the field of critical thinking to discuss their work and experiences. These projects brought home how challenging it is to think critically in times where it matters most, when our emotions, values, and biases are in constant play—something TWI could well attest to.

In 2001, I initiated The Dialogue Project to explore how group dialogue that models curiosity, empathy, and clear reasoning can help people build the skills and relationships to overcome that challenge. I contracted with a range of nonprofit organizations to learn how they were using dialogue processes in different aspects of their work. These collaborations confirmed we were moving in the right direction in terms of focus (dialogue) and approach (supporting and learning from a diverse set of nonprofits and their leaders).

In 2004, Fred passed away at the age of 90. He was a one-of-a-kind character with many wonderful qualities: boundless curiosity; a quick sense of humor; a lack of pretense; and at times a surprisingly generous spirit. He also had other qualities that made him quite difficult to deal with. And while those parts of him made it challenging to maintain a relationship with him, we remained close until the end.

One reason he came to trust me, I think, is because I never lost my sense of empathy for him and his personal struggles, including his struggle to find his own voice. He also knew that I genuinely shared his passion for TWI’s mission. Though we had our share of “the emperor has no clothes” dynamics, we shared a real connection around that. And so, when he passed, he left me in the position to lead TWI.

From the time I started, I had a long-term vision that TWI could be a thoughtful, innovative, maybe even influential foundation—and that vision sustained me over the years when the going got tough. In important ways, my tenure at TWI felt like a long incubation period of learning and reflection. Now, the time to blossom was at hand. It was liberating to feel that TWI could finally start to realize its long-dormant potential—and to do so in ways that remained loyal to Fred’s best intentions and core questions.

Act II

Following Fred’s death, I led a process of internal renewal at TWI. We rebuilt our board and Pia Infante joined me on staff in a part-time capacity. Though TWI had had a strong living donor and the accompanying feel of a small, family foundation, there were no family members on our board. In looking ahead, we saw that we were truly an independent foundation.

I also raised the question of perpetuity with our board, asking whether it made sense for TWI to manage its resources in order to exist indefinitely. I didn’t think we were ready to answer that question yet, but I wanted us to continually revisit the assumption that perpetuity was the only way or the right way to run a foundation.

In 2005, TWI switched from an operating to a grant-making foundation for two primary reasons. First, giving grants to aligned nonprofits rather than hiring people to work on our own projects would better serve our mission. Second, I wanted TWI to contribute to a larger philanthropic conversation about what and how people fund, and I thought we could do this more effectively as a fellow grant-maker rather than as a stand-alone, operating foundation.

Given our relatively small size, we decided to be a proactive grant-maker and not accept unsolicited proposals. Being well acquainted with some of the power dynamics that can come from working for a person of wealth, I also wanted TWI to minimize the hoops people had to jump through to receive funding. It made inherent sense to me that we should give unrestricted grants and minimize paperwork.

I soon learned how much people appreciated and valued ongoing, general operating support, especially when it was coupled with an invitation to have more than a transactional relationship. I felt humbled and grateful that being a grant-maker enabled me to learn from and build relationships with such a range of talented, committed, inspirational people.

My initial grant recommendations reflected TWI’s generalist perspective. From classrooms to prisons, neighborhood centers to rural retreats, film screenings to town halls, I was interested in where dialogue was being used with passion and purpose. Some of our early grantee partners had been part of The Dialogue Project that TWI had run for many years. Others I read about and researched. As TWI’s network of relationships grew, so did recommendations from others about possible connections.

Our early portfolio was weighted toward organizations working in education, civic engagement, and leadership development. As time went on, we became more attuned to community organizing, film, and journalism. Emerging developments in networks, human rights work, social movement-building, and peer learning confirmed for us that the moment was ripe for our mission. One could infer from our grants portfolio that we didn’t believe in process for the sake of process itself, but that most of our work was oriented to addressing systemic inequities and advancing social good.

I also thought that having an eclectic portfolio of partner organizations held promise in terms of convening people to connect and cross-fertilize ideas and experiences. In April 2005, we brought our grantee partners together for a one-day gathering at TWI’s office. Participants valued the experience but gave us the feedback that if we wanted people to really get to know each other, we should hold a weekend retreat in the future. So, we did.

Our first retreat in 2007 brought together 30 leaders of grantee organizations, TWI board members, and staff to build connections and relationships. The feedback was very positive. One thing we couldn’t help but observe was what a white, and a generally older, group we were. We resolved to be more intentional about creating a more inclusive and diverse group going forward.

Over time, we held six more retreats, learning, growing, and becoming a more diverse network with each one. Our retreats became a signature event of ours and evolved to include over 100 participants including current and former grantees, other funders, affinity group leaders, and other kindred spirits. I always had to pinch myself at these gatherings for they were dramatic and heartfelt reminders of how far we had come as a foundation and how fortunate we were to be connected to such a wonderful community.

In 2011, we moved beyond questioning the assumption of perpetuity and set 2022 as our ending date. To us, setting a limited life would enable us to be more responsive, strategic, and impactful.

Having made that decision, we thought a good first step for us would be to get more concrete feedback on our work and approach and so we commissioned the Center for Effective Philanthropy to conduct a Grantee Perception Report for us in 2013.

The positive feedback we received from the GPR about how we made grants, the quality of our relationships, and the support we provided beyond the check was deeply gratifying and affirming. CEP highlighted a theme that emerged from people’s comments: how important it was that they felt trusted by us.

We also took to heart a call to action that came through strongly from those we supported: they urged us to make the case within philanthropy for what and how we fund and tell our story and the stories of those we support in ways that help shift philanthropic practice.

We took that charge seriously and decided we needed more internal capacity to act on what we heard. Consequently, the board invited Pia, who had contributed to TWI in so many key ways in a part-time and contract role for nearly 10 years, to join me as Co-Executive Director in July 2014. Knowing how well we worked together and what a great thought partner she was, I was thrilled when she said yes.

There were major transitions on our board as well in 2014, with two treasured, long-time trustees stepping down, and two exciting new members joining our team. These transitions, combined with the resolve to act on what we heard from our grantees, signaled to me the end of TWI’s second act.

ACT III

Though still some years away, the fact that TWI would end sharpened our focus in terms of thinking more strategically about how we might influence the field. We saw our strength as building relationships through individual and group conversations that offered opportunities for peer learning and reflection, so we decided to play to our strengths through relational organizing.

Though we had spoken and written about how we did our grantmaking for years, we hadn’t called it anything; it was just what we did. That changed when Pia took the lead in naming and framing our approach as Trust-Based Philanthropy and breaking it down into concrete steps funders could follow.

We recognized that the steps we were naming weren’t new, so we held the frame lightly; it was really an organizing framework to invite peer learning and prompt people to shift their philanthropic practice. For a while, we were this approach’s sole proponents, with Pia, in particular, doing the heavy lifting out in the field. That changed dramatically, however, when first the Robert Sterling Clark Foundation and then the Headwaters Foundation joined us as allies and advocates. Together, we set in motion the development of The Trust-Based Philanthropy Project, a collaborative five-year initiative launched in January 2020 that has become a core part of TWI’s legacy.

Alongside that effort, we continued to learn from and be inspired by our grantee partners’ wide array of creative and dedicated efforts and to offer to be of service to them in any way we could, including connecting and convening, opening doors to other funders, being a sounding board, offering feedback when invited, making our space available for meetings and reflection, being an advocate for the work – really, just showing up for our partners at different times and in different contexts. It was important to us to offer an invitation to relationship, not a requirement.

The invitation to relationship manifested in another way as long-time board members continued to transition off the board and, aside from me, we became an entirely new team than the one that had made TWI’s decision to spend out. That we changed from a largely white boomer board to a majority people of color and younger board was an important part of TWI’s evolution.

We evolved in other ways as we adapted to the changing current of events around us. The election of 2016, the onset of the COVID pandemic, and the country’s racial reckoning spurred us to direct more funds to efforts to build power and address inequities in BIPOC communities. In doing so, we participated in more collaborative funds than we had in the past. If we weren’t spending out, this might have been one area (there are others) we would have continued to explore.

As TWI ends, we’re still very much in process. If we weren’t closing our doors, we would keep evolving. We might have grown and evolved by making our investment portfolio more mission-aligned and implementing more participatory grantmaking.

Although there are ways of working we might wish we could continue to explore, our journey has only underlined for us the value of setting a limited life. It enabled us to achieve a level of impact and visibility and provide a level of timely support that wouldn’t have been possible following the status quo course of 5% annual spending. As one of our board members observed a few years back, “Our impact is increasing as our endowment shrinks.” We hope our story, along with those of other sunsetting and limited life foundations, will open other funders’ imaginations to what becomes possible if you truly open the purse strings.

Having been at TWI for 34 years, I am humbled, proud, and deeply grateful to reflect back on how far this “quirky” foundation (an affectionate description from a long-term partner) has come from where it started.

TWI’s founder, Fred Whitman, held tightly to his sense of “I” when it came to the Institute and the power he held. Some have said that in a sense I was TWI’s “second founder.” What has been profound learning for me is that as I gave up some of my own personal power (e.g. Pia becoming co-ED, me taking a back seat with new board invitations), we became a more powerful organization.

My long-term vision for the Institute would never have been realized without the “I” becoming a “We.” That TWI’s “We” grew to include such a wonderful community of people is beyond what I first imagined was possible in those fraught days with Fred.

Finally, I don’t think TWI would have lived into our aspirations the way we did if we hadn’t embodied the dialogue, relationship building, and inclusive leadership named in our mission. In these times of great challenge, complexity, and uncertainty, it seems to me more important than ever that as we make the road by walking, we walk our talk along the way. And do so with loving and generous spirits.