Trust As A Starting Point

What if we as funders started with trust, instead of making potential partners “earn” it? Vu Le starts our sibling blog posts today by questioning the assumption that grant seekers need to prove their basic trustworthiness to funders. Indeed, up-ending this premise has been inherent in TWI’s approach since we started making grants.

TWI’s 9 Practices of Trust-Based Grantmaking emerged from feedback we received from our grantee partners in 2013 when we asked: How should we focus our energies in the decade before we Spend Out? In no uncertain terms, we heard from our partners that if we could persuade other funders, donors, and investors towards these practices at any scale – our spend out would be more meaningful to them.

Here are a few current reflections on the most significant of the practices:

Multi-Year General Operating Support Never Goes Out of Style

It’s possible that Vu fell out of his chair when we shared that our 9 Practices are fundamentally based on multi-year, unrestricted, general operating support. In 2014, GEO reported slight increases in the number foundations electing to provide general operating support, but, at 25% of 637 grantmakers surveyed, it is still far from the norm. We continue to be struck by how much this type of support lays the foundation for trusting relationships and effective action.

As I’ve stumped about this lately, I’ve been challenged to imagine that flexible funding or capacity building funds could be more useful to an organization than a commitment of multi-year general operating support – depending on context, scale and timing. Of course there are other types of funding structures that are useful. Directed, strategic funding for collaboration, convening, or to move a specific policy agenda are just a few examples. But when it comes to alleviating the immense pressure on our most visionary leaders to raise money, long term funding commitments are vital. Plus, most grant seekers are not in the position to say anything but “sure, your [fill-in-the-blank] funding strategy is brilliant, thanks.”

As I’ve stumped about this lately, I’ve been challenged to imagine that flexible funding or capacity building funds could be more useful to an organization than a commitment of multi-year general operating support – depending on context, scale and timing. Of course there are other types of funding structures that are useful. Directed, strategic funding for collaboration, convening, or to move a specific policy agenda are just a few examples. But when it comes to alleviating the immense pressure on our most visionary leaders to raise money, long term funding commitments are vital. Plus, most grant seekers are not in the position to say anything but “sure, your [fill-in-the-blank] funding strategy is brilliant, thanks.”

What I’ve understood from many leaders over the years is that multi-year general operating support AND capacity building AND targeted flexible support (for things like convening) are optimal. We can see the long term, powerful benefits of a “Both/And/And” approach in Haas Jr’s Flexible Leadership Award Program.

At TWI, regardless of the precise type, the underlying question is this: Does the funding structure free up the leadership to move more creatively, nimbly, effectively?

This doesn’t mean there is no benefit to offering Support Beyond the Check, as funders can be valuable resources for organizational strengthening, leadership and burn out support, opening doors, field and landscape scans, convening and connecting, and much more. In these instances, I would ask us to Partner in a Spirit of Service and demonstrate that we can be trusted with our partners’ honest disclosures about the messiness and complexities of change work.

Field Notes About We Do The Homework

Given TWI’s Spend Out, and limited grants budgets, the first and most essential filter for We Do the Homework is to be clear with ourselves about who we are looking to partner with and how many such partners we can realistically take on, especially in light of current multi-year commitments. In practice, this means we are a pro-active funder.

Given TWI’s Spend Out, and limited grants budgets, the first and most essential filter for We Do the Homework is to be clear with ourselves about who we are looking to partner with and how many such partners we can realistically take on, especially in light of current multi-year commitments. In practice, this means we are a pro-active funder.

We seek partners working towards equity whose fundamental programmatic strategy is to cultivate dialogue, critical thinking, reflection and relationship. We also seek partners who are unconventional ambassadors of a process-oriented approach in new networks, since TWI’s aspiration is to lift up the importance of these values (and how they manifest in grantmaking and investing) in the public sector.

TWI’s profile is somewhat distinct, since we are not solely funding in a specific geographic or issue area. Our portfolio is eclectic, and we appreciate the cross-pollination that comes with it. We proactively seek out potential grantee partners, and consider ones referred to us through our networks as well as those who find us themselves. In the case of Rainier Valley Corps we’d been avid readers of the Nonprofit With Balls blog (where Vu writes with piercing honesty about the opportunities and challenges that accompany non-profit executive directorship) and several trusted philanthropic and nonprofit colleagues had recommended we talk with Vu.

Before meeting, we do our best to understand the organization’s purpose, strategies, programs, leadership, and financial standing through available public record (e.g. websites, 990’s, annual reports, published articles, etc.) and asking within our nonprofit and philanthropic networks. This looks a bit like heavy internet stalking and informal conversations with colleagues about the prospect. Also, we are known to read documents that require downloading, extensive email attachments, and text without pictures. It’s not uncommon for a potential or current partner to say, “Oh, you read it?!”

Having grounded ourselves in this way, we meet with the leadership to learn more about potential fit – with a deep commitment not to waste a leader’s time in protracted process. In Vu’s case, we met a couple of times. We listened, we shared our aspirations, we asked each other big questions, we dialogued about themes in Rainier Valley’s story that resonated, and we tangibly experienced a deeper alignment of values and purpose. By this I mean we experienced Vu embodying TWI core values as well as having similar aims to shift practice in the philanthropic and nonprofit sectors. This was the relational, experiential additive to our pre-meeting homework that concretized an initial sense of good fit into formal partnership.

Having grounded ourselves in this way, we meet with the leadership to learn more about potential fit – with a deep commitment not to waste a leader’s time in protracted process. In Vu’s case, we met a couple of times. We listened, we shared our aspirations, we asked each other big questions, we dialogued about themes in Rainier Valley’s story that resonated, and we tangibly experienced a deeper alignment of values and purpose. By this I mean we experienced Vu embodying TWI core values as well as having similar aims to shift practice in the philanthropic and nonprofit sectors. This was the relational, experiential additive to our pre-meeting homework that concretized an initial sense of good fit into formal partnership.

Recycling Pre-Existing Proposals and Reports

We agree with Vu that a universal, standardized application would be fantastic. I’ve also heard from many colleagues that each institution has its own priorities and idiosyncrasies. Carrie Avery, Durfee Foundation’s President, reminded us last year to be creative over conventional. While we may still need some kind of documentation, we don’t need all proposal processes to be time consuming on both the production and review ends.

We ask potential grantee partners to send already existing material – and then tailor it to our own needs and format. We find out what’s important to our own stakeholders, then aggregate that information (and experience) by any means necessary except asking grant seekers to spend tens of hours in application land – online or on paper. Of course, many foundation staff colleagues share that this is already standard practice. Thank you! We see you! Keep fighting the good fight.

Feedback is the New Black

There are so many encouraging efforts in the philanthropic sector to enhance the practice of soliciting feedback from investees for their donors, funders, and investors.

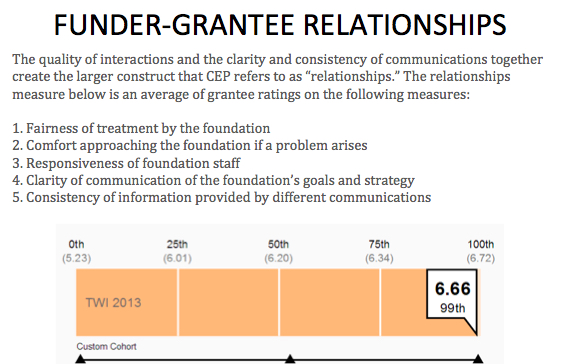

I applaud the foundations that publish their Grantee Perception Reports and ask to be held publicly accountable toward improvement, like the Irvine Foundation’s 2015 report. If a formal evaluation process seems cumbersome, feedback flow can be less formal. The Peery Foundation asks everyone to complete a quick survey of every interaction (digital or in person) to encourage a continuous feedback loop.

Ultimately, we build trust when we listen and act on what we hear — or at least communicate back why we cannot.

Mea Culpa in Conclusion

In reviewing our Grantee Perception Report findings, I see that TWI has been falling down on the job on a request from our grantees to convene them more consistently and less formally. Our people want to be together and we have renewed our commitment to creating opportunities for that to happen.

I share this anecdote to end on this note: TWI is far from perfect. We fumble and try to learn from our missteps. We seek to embody our values and demonstrate these 9 Practices, but perfect certainly doesn’t need to be the enemy of the good. We don’t expect that every other funding institution will be able to adopt all the practices wholesale. Even those foundations that share trust based principles and practices may have constraints on how much they are able to implement.

Regardless of institutional obstacles, though, we all have a circle of relationships in which we have direct impact. What we embody in our communications and relationships may immediately impact hundreds or a handful of people. The truth is we can be agents of a trust based approach by practicing within the relationships in which we already operate.

That said, we hope that something within these sibling blog posts about Trust Based Grantmaking will inspire our funder colleagues and their institutions to answer the following questions:

How can our grantmaking start with trust?

Where can we adjust to take on more of the responsibility for determining good matches and fit?

How and when are we willing to learn if our actions match our values?

How might we embody the values of equity and humility in ways that serve our collective aspirations to arc towards a more just and equitable world – for ourselves, our planet, and our people?