A Mismatch Between Need and Affluence

This article was first published in The Chronicle of Philanthropy, we thought it would be a good one to share.

American communities with high standards of living often have low charitable giving rates, a new Chronicle analysis finds.

Text by Rebecca Koenig and visuals by Meredith Myers

In a state with a moderate standard of living, Collin County, Tex., stands out.

The suburban area north of Dallas has a median household income of more than $79,000, 64 percent higher than the state average. In September, Money magazine ranked the county seat, McKinney, the best place to live in America.

But as a racial incident in McKinney that drew national attention revealed, not everyone who lives there enjoys its resources equally. Responding to a disturbance call at a community pool, a white police officer brandished his gun at several African-American teenagers and pinned one girl to the ground.

Racial and economic divides may affect life in McKinney in ways subtler than police violence. They may blind people to their neighbors’ need.

Despite Collin County’s general affluence, high levels of employment, and on-time secondary-school graduation, there’s one arena in which it doesn’t perform well: charitable giving as a proportion of income. Its residents give just 2.94 percent, less than all neighboring counties and the state average of 3.59 percent.

It’s a common combination across the country: Residents of areas with high standards of living, low poverty, and low crime give less to charity than those in less well off areas.

That’s one finding from new data, compiled by The Chronicle of Philanthropy, combining giving behavior with quality-of-life measurements for 2,670 counties across the United States. It’s based on data from The Chronicle’sHow America Gives study, which shows the share of income Americans in different parts of the country have donated and the Opportunity Index, created by two antipoverty nonprofits, which assigns scores of socioeconomic well-being to counties based on measurements such as housing costs, preschool attendance, Internet access, and percent of residents with advanced degrees.

The inverse relationship between opportunity and giving is “a compelling, counterintuitive finding” that pushes against our assumptions that “places with higher scores would have higher rates of giving,” said Russell Krumnow, managing director of Opportunity Nation, one of the nonprofits behind the Opportunity Index. “We really need everyone’s hands in this work, and the work of expanding opportunity is everyone’s.”

The new data raise questions about whether donations lead to improved quality of life in communities and whether people who are well off are less inclined to give to others.

There are some caveats. The Chronicle’s study is based on 2012 tax data from Americans who itemize their deductions. While it represents 80 percent of all donations in the United States, it doesn’t capture the giving behavior of people who don’t itemize (often those with smaller incomes), people who give more than the itemization limit (often those with higher incomes), and people who have wealth but no reportable income.

People in areas that give generously could be steering their donations outside of their counties to places that are poorer or to arts or medical-research causes that don’t affect the opportunity score. And the total amount people donate in wealthy areas is often larger than the amount given by those who live in less affluent regions.

Still, Yvonne Booker, executive director of the Assistance Center of Collin County, thinks people who live in wealthy communities may be missing opportunities to make significant improvements in their neighbors’ lives.

Her organization relies on donations to provide emergency financial aid to families facing eviction or suspension of utilities. The county’s needy population is not overwhelmingly large. For example, a recent tally found that of a total population of 885,241 people, 367 people were without a permanent residence, spending the night on the street or in shelters, hotels, or hospitals. It would cost relatively little to provide housing for all of them, Ms. Booker said.

“One of the things that I would hope communities like ours would really grab ahold of is: We can move the needle here,” she said. “Don’t ignore your need, really address the need and celebrate the success you’ve had in moving the needle.”

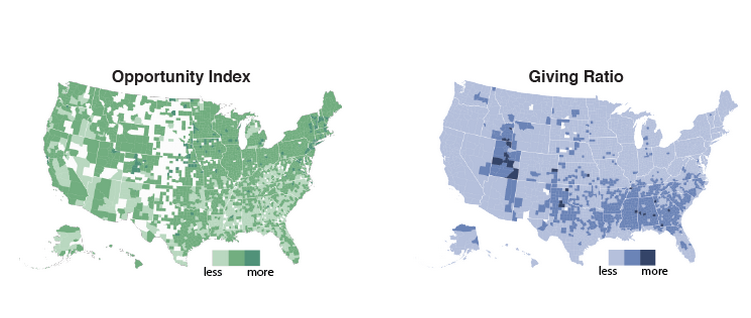

Mapping Giving and Need

The Giving Ratio map shown here indicates the share of income people donate to charity. The Opportunity Index map displays standard-of-living scores in counties across the United States based on 2014 data that include the unemployment rate, median household income, percent of people living below the federal poverty line, percent of adults with at least an associate’s degree, and the percent of households spending less than 30 percent of income on housing costs.

The Chronicle combined those two maps to show how the giving rates and opportunity measures intersect in each county. Overlapping the maps shows all combinations of low, moderate, and high values for donations and opportunity indicators.

The resulting interactive map shows that counties in New England tend to have low giving and either moderate or high standards of living, while those in Florida, the Mid-Atlantic States, the upper Midwest, and the West Coast tend to have low giving and moderate standards of living. Counties in the Southeast tend to have moderate giving and either low or moderate standards of living. Both giving and community well-being are moderate in counties in Utah and the southeast corner of Idaho. A few counties in the Southeast and Utah and Idaho have high giving ratios.

Put your cursor over a county on the interactive map to see its opportunity index and giving ratio scores. (Data is unavailable from several counties in Texas and in Great Plains states because of their small population sizes.)

Beyond the Map

What motivates people to give? The map doesn’t offer a conclusive answer, but it does provide hints about how to encourage generosity in affluent counties. Just as place affects the odds of achieving upward mobility (as a study covered by The New York Times found), it affects attitudes toward giving.

Local giving behavior may depend on the prevalence of nonprofits in each county, said Nathan Dietz, senior research associate at the Urban Institute’s National Center for Charitable Statistics.

“When it comes to volunteering, if it’s hard to find an organization to volunteer with, you might not do as much,” he said. “When it comes to donating money, I think probably the same factors are taking place.”

But more organizations may be worse than fewer, Ms. Booker said. Collin County, for example, had 970 registered nonprofits fill out 990 tax forms in April 2015, the sixth-highest number for all counties in Texas, but the percentage of income that residents give — 2.94 percent — is in the state’s bottom quarter.

Ms. Booker hypothesized that because Collin County’s many nonprofits tend to duplicate others’ efforts, “people are not quite sure what to give to, so they chose not to give or give conservatively.” In other parts of Texas where she has worked, people gave at higher levels to organizations they felt provided comprehensive community care.

People who are religious tend to give more to all kinds of causes, many studies have found, and a strong sense of faith is more prevalent in certain regions, such as the Southeast and Utah, where the large Mormon population is encouraged to tithe, or donate 10 percent of their incomes to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

“Faith-related giving has to be acknowledged as a principal driver among the motivations for people who give back,” said Brent Christopher, president of the Communities Foundation of Texas, which serves Collin County. “They do give back to their churches and synagogues and mosques in a major way.”

Religion doesn’t always explain giving, though. A smaller percentage of people in Lamoille County, Vt., identify as religious than in its five neighboring counties, which have significant Catholic populations. It has similar demographics — overwhelmingly white and liberal — and similarly moderate opportunity scores. Yet its residents gave nearly 4.5 percent of their incomes to charity, higher than that of all other counties in New England.

Dawn Archbold, executive director of the United Way of Lamoille County, says people in this “friendly, giving, liberal community” take pride in their 10 small towns, and because they know their neighbors, they give.

“It’s very, very close-knit,” she said. “Everybody knows everybody, too. I think that really helps. If there’s someone in need in the community, everybody knows about it and rallies to help.”

As an example, Ms. Archbold points to the Lamoille Area Cancer Network, a popular charity that helps patients get to chemotherapy and radiation appointments and take care of other needs. When Ms. Archbold had cancer, volunteers drove her to the doctor’s office every day for more than seven weeks.

“It almost seems like we have the same mind-set,” she said. “I’m in awe of it all the time.”

Creating Community

A shared sense that everybody has a role to play in the common good, then — more than just religious belief — may encourage generosity. That’s what David Campbell and Robert Putnam concluded in their 2012 book American Grace: How Religion Divides and Unites Us, which argues that people with tight community networks tend to give more to charity.

“Places where you find higher social capital — trust that is built between people when they associate with one another, perhaps through groups — where people are more likely to trust those around them, are more likely to contribute to the public good,” Mr. Campbell said. “The religious boost to giving, both time and money, is true both for religious causes and also secular causes. The more church friends you have, the more likely you are to give.”

Mr. Krumnow of Opportunity Nation hypothesizes that people with lower incomes may be willing to give because they identify closely with the challenges facing others in their communities. But social capital and neighborly empathy are sometimes missing in wealthy counties, where a veneer of affluence may mask struggling residents and persuade people there’s no need to donate to social-service organizations, nonprofit leaders say.

For example, people in Collin County were surprised by the homelessness count after it was published in local newspapers, Ms. Booker said.

“We got calls from people saying, ‘We have no idea we have people living in their cars,’ ” she said. “You can drive in areas in Collin County, and you don’t really see it.”

San Francisco County has a similar problem, said Karl Robillard, a spokesman at St. Anthony Foundation, a 65-year-old nonprofit that provides meals, a health clinic, and a clothing-distribution center for low-income families. The area’s tech boom and high-paying jobs are attracting young people who aren’t familiar with St. Anthony’s work and may be insulated from poorer residents, who are hurt by the area’s rising costs of living.

Raising awareness among San Francisco’s newcomers is high on the nonprofit’s priority list. It has built partnerships with technology companies, and when their employees come to volunteer, St. Anthony’s staff members educate them about the lives of the nonprofit’s clients. Catherine Kelliher, donor-relations senior manager at St. Anthony’s, said volunteers are taken aback to learn that 2,400 meals are served daily.

“Seeing it is really half of it,” she said. “When I take folks on tours, they’re always a little bit blown away.”

There’s anecdotal evidence that the up-close-and-personal approach is working: At the end of volunteer sessions, Ms. Kelliher said, some volunteers make donations, and others work with their employers to make matching gifts.

And sometimes, once people’s eyes are opened, they give big. When Eric Barrett, a Facebook engineer, lived across the street from St. Anthony’s outdoor-clothing distribution site, he saw hundreds of people lining up every day for shirts and pants. That daily scene compelled him to donate more than $140,000 in Facebook stock to the nonprofit.